“It Couldn’t Not Happen”: ross brubeck on Ministry, Fire, and the Walk to Washington

- windycooler

- Jul 30

- 7 min read

ross brubeck knows what it feels like to be called.

“It was an overwhelming physical feeling that I couldn't express properly,” he says, “and had to come out in some way which felt like just a—just the tiniest fraction of the truth that I was experiencing.”

That’s what public ministry feels like to ross—not a job or a role, but a force that demands expression. "It's undeniable. It feels like, when I saw The Flintstones movie in the 1990s [as a kid] and was so charged up by the experience... I just needed to do something about it, because I just felt so like, enormous on the inside."

ross, originally from Sandy Spring Friends Meeting (Maryland)—the same meeting where my ministry is held—now worships with the Brooklyn Friends Meeting (New York). His ministry in recent years has centered on a bold and beautiful act of public witness: the Walk to Washington. That 2025 pilgrimage was more than a protest. It was a modern Quaker revival, a collective expression of Spirit through foot, breath, prayer, and protest.

This is the story of that walk, and of what ross—and those walking with him—have learned about ministry, community, money, tradition, and the urgency of being faithful to the fire within.

A Fire That Cannot Be Denied

For ross, the call to ministry is visceral, even explosive. “The drive to actually make the Walk to Washington a reality was fire,” he says. “Fueled by the same, yeah, by that same kind of fury... it was something that couldn't not happen.”

The momentum of that call “just kind of like brushes aside all of the doubt that I would feel when going into something like this.” It’s a powerful testimony to what it means to be spiritually led—when something has to be done, not because it’s strategic or reasonable, but because the Light has made it clear.

Listening to ross I began to realize that a call to public ministry sometimes feels like “when you realize that you're in love... it can feel like the urgency of falling in love.” ross echoes this: “If it is kept inside for too long, it’s going to do more than just spoil. It’s going to…it’s gonna rot, and that feels like a disservice... not doing everything I can right now to invite the world to share this experience.”

And so, ross walked.

A Walking Witness

The Walk to Washington was a several months-long effort of preparation, prayer, and discernment. It was, in ross’s words, “a longer form message brought into the world,” a deliberate act of ministry rooted in the Quaker tradition of protest and prophetic witness.

The walk was inspired in part by the 1657 Flushing Remonstrance, a foundational document of American religious freedom, written by settlers who refused to condemn or persecute Quakers. One line in particular lit the fuse for ross and his fellow organizers:

“We cannot condemn them... for out of Christ God is a consuming fire, and it is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.”

The walkers saw a parallel between the Remonstrance’s call for religious liberty and current threats to immigrants, people of color, and the sanctity of houses of worship.

In response, they wrote the 2025 Walkers Remonstrance, which declared:

“We cannot accept this transgression of the sacred; both the sacred stillness of our worship, and the divine human rights of our persecuted friends.”

They wrote:

“We know the truth: that we are all children of God, deserving of equal opportunity and safe harbor... When forced to choose between the laws of man and the Law of God... we will always choose to follow The Light.”

The walk was more than symbolic. It was grueling and real. ross describes the “scale of the action” as the only thing that matched “the amount of physical sensation” he had when contemplating the ministry. Each step became worship. The walkers created a new kind of congregation: one that gathered daily, moved together, and lived their faith moment by moment.

Brooklyn Meeting provided free office space, a vital form of support that ross describes as “material enablement.” But in many ways, the organizers were flying on faith—and very little else.

A Wealth of Tradition, a Poverty of Funds

ross’s return to Quakerism, after a decade away, felt like re-entering a stream that had been flowing around and through him all along. Introduced to the faith as a young child, he describes it as a “project started for me a long time ago.” But it was during the pandemic, in a time of isolation and loss, that ross recognized the enormity of his spiritual inheritance: “a wealth of tradition and a wealth of methodology for accessing spiritual interiority.”

This deep interior space fueled his public ministry. And yet, sustaining it proved painfully difficult.

"The amount of money that I had saved up in New York was enough to sustain me for the four months that it took to plan the walk and then execute the walk,” ross shares.

“And I find myself on the other side of it not knowing... not knowing what the hell to do.”

Grants helped, and donations helped, but the hours were unpaid. The spiritual energy was infinite—but the economic reality was not.

“If there was money that was available to us now that would sustain us all until the next action happened,” he says, “then we would be planning it right now. We're just not able to.”

There’s a deep cost to that kind of precarity. Describing the way in which he needs to carefully consider how to feed himself: “How much does this bread, plus this meat, plus this vegetable, cost—that takes up so much spiritual energy that it leaves nothing left afterwards.”

The problem is not just financial. It’s cultural. In Quaker circles, simplicity is a virtue—but ross names the shadow side. “It feels ghost-like,” he says. “It feels wrong to ask for money. I've been taught that it is wrong to have more than I have learned to survive with.”

This is not just his burden. It’s generational. “We're not inheritors of the same economic world that these other prior generations had... this ambient amount of money that existed in the United States, for certain people, made a lot of prior actions possible.”

The Generational Divide

ross speaks openly about the demographic truth many of us sense but struggle to name.

“The median age of Quakers aren't the type to support something so energetic,” he says bluntly. “Quakers are old, is what I'm saying.”

There’s a “really serious gap between how many folks in the meeting have white hair and how many folks are younger... and the folks in the younger cohort? Not very populous.”

And yet, there is hope. There is “a surplus right now, in folks who are younger and folks who are looking for something.” These are people who long for “the more ineffable qualities of a faith-based society”—who are ready to act, to walk, to love, to serve.

But they need structures that can hold them. “Without the proper support structure,” ross warns, “it will not grow.”

Carrying the Fire Forward

The walk was a kind of revival. And like all revivals, it was fleeting—and powerful—and fragile.

Each day since, ross says, “we’re a day further from the actual reality of being immersed in that energy of the walk, and perhaps a day further into the spirit of it fading.”

Sustaining that spirit takes more than vision. It takes rhythm. It takes money. It takes community.

And yet: the Light still shines.

The 1657 Remonstrance declared, drawing from the biblical book of Matthew, “Desiring to do unto all men as we desire all men should do unto us... this is the law and the prophets.”

The 2025 Remonstrance echoed:

“Whoever may come to us in fear and in need, we are compelled by conscience to aid them, giving them free access to our homes and churches.”

This is the spiritual lineage ross walks in.

His fire—like so many younger ministers today—burns with the memory of early Friends, with the urgency of love, with the vision of a faith that still knows how to move its feet.

ross reminds us that the scale of spiritual feeling, if ignored, rots. But when expressed—when walked—it revives the world.

ross brubeck is considering what is next in his call to ministry and how to labor with the Religious Society of Friends to support the call so many peers feel right now, but cannot imagine how to survive.

I talked to him during Summer Sessions of New York Yearly Meeting in 2025.

Next week we will hear from Angela Hopkins, an elder in New York Yearly Meeting, who I also spoke with during their recent Summer Sessions.

From the hidden costs of ministry to the spiritual dangers of guilt and perfectionism, her testimony is both a challenge and a balm. As she asks, “If the water is essential, what must we do to purify our pipes?”

We are experiencing overwhelming demand for our work at the Friends Incubator and need more funding to meet this demand.

One of the ways you can support us is to visit our "cute stuff store" where we have a few adorable pieces available, including crop

tops, hats, t-shirts, onesies, mugs and stickers.

We get about 50% of the purchase price, which goes directly into our operating expenses and which we spend right away to create programming, support the staffing of our wildly popular new fellowship program, and provide this weekly blog to every Friend, all free of charge. We're living into Luke 12:24-28, considering ravens and wildflowers and walking in full faith as ministers (and pirates) in our communities.

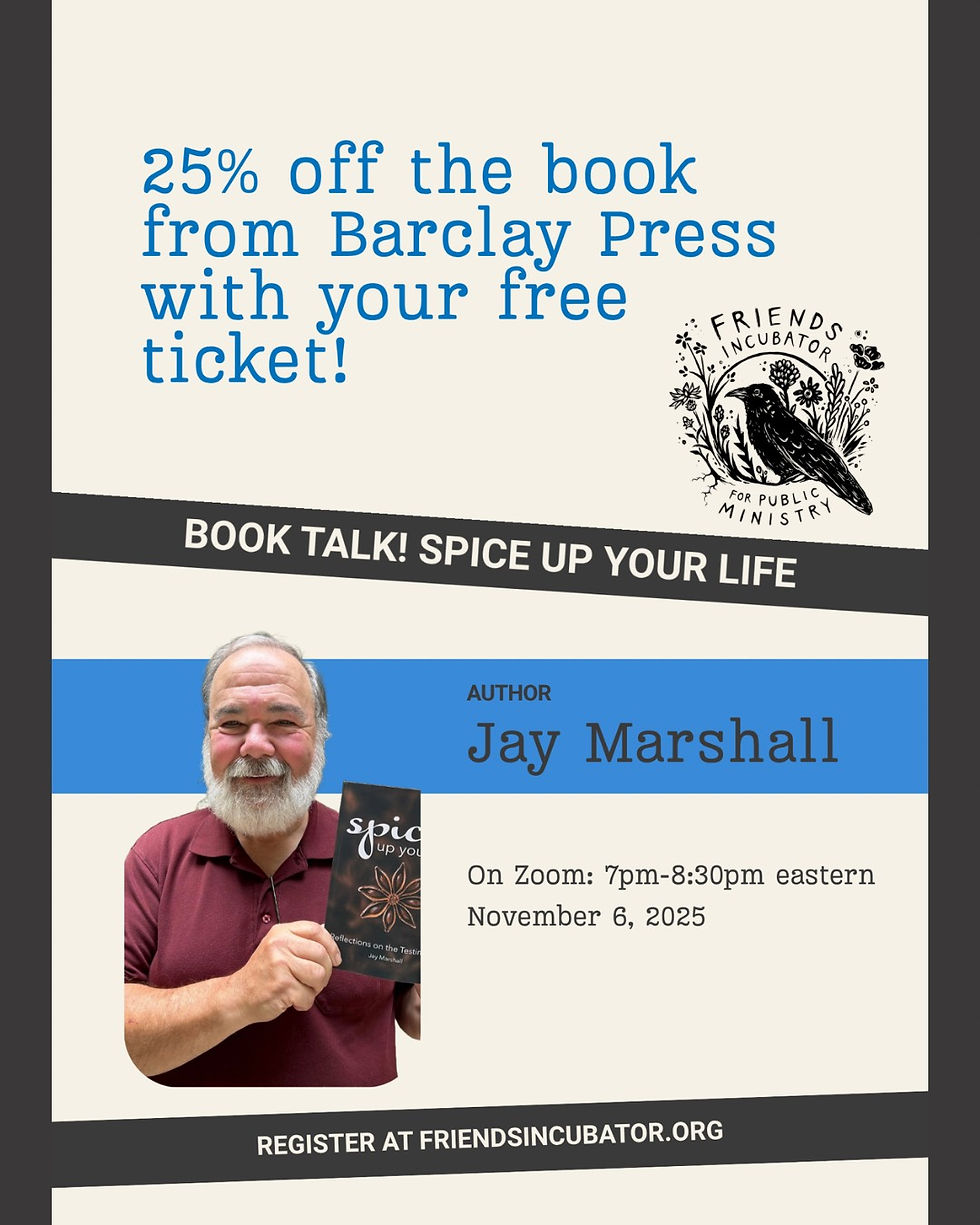

Upcoming!!

Comments